Downloaded from IMSLP library. Editor: Günter Haußwald, 1958.

Johann Sebastian Bach, or J. S. Bach (1685–1750), is well-known as one of the most prominent composers of the Baroque period, if not of all time. With a massive volume of compositions, comprising of Cantatas, Sonatas, Organ works, Clavier works, Chamber music and music for other minor instruments. He was most known for his technique and extensive use in counterpoint (i.e., melodically independent but harmonically codependent). This technique is clearly evident in the two books of the Well-tempered Clavier, where he wrote a set of Preludes and Fugues encompassing all keys of the twelve tones. But there's more; just when we thought writing contrapunctally for key instruments was hard enough, he (J. S. Bach) was able to achieve the similar levels of polyphonic harmony for string instruments (i.e., cello and violin), which were thought would only serve the melodic/lyrical compoment of a music piece, or could only be polyphonic when played as an ensemble.

The achievement I was referring to previously is the work for solo violin, numberred BWV 1001 to 1006. This big work consists of six smaller works, three sonatas and three partitas, with the numbering as the following:

In layman terms, a sonata is a work played by an instrument with different tempi or composition styles. For example, the second sonata BWV 1003 contains four movements: Grave (slow), Fuga (fugue), Andante (pacing), and Allegro (fast) in that order. A partita, on the other hand, is a set of Baroque dances, therefore rhythm being the major focus of a partita. Each dance may originate from different regions or/and have slight variations, which provide sufficient flexibility for Bach to compose. For instance, the second partita BWV 1004 has 5 movements: Allemanda (a German dance), Corrente (a French dance), Sarabanda (a Spanish dance), Giga (an Irish dance), and lastly Ciaccona (a Spanish dance).

Although all sonatas and partitas have been widely arranged for and played on the guitar, it is undeniable that the last movement of the second partita, i.e., the Ciaccona (used interchangeably with Chaconne) from BWV 1004, is played the most. This could possibly be the a consequence from the "Segovia movement" in the 20th century. The evolution of the guitar from a folk instrument to a concert instrument led by Andrés Segovia (1893–1987) resulted in a massive flux of new compositions and arrangements of early-period artists such as George Friderich Handel (1685–1759), Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687–1750) and Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757). The Chaconne from the second violin partita definitely was not an exception. The premiere of Segovia's version of the Chaconne in 1935 brought his transcription to international recognition quite immediately (Wade, 1985). This transcription is the start for many more to come in the future, both in the style of Segovia and contemporary/modern era.

The Segovia school. Being one of the first guitarists to use fingernails rather than the fingertips, Segovia exploited the tone created by the nail to its full extend. Fast-plucked, sudden, projective chords were heard in almost every Segovia's playing. He was also quite (in)famous for his tone colors (mostly when play closer to the fretboard) and overly-executed vibrato. Additionally, the use of rubato was significantly recognizable compared to other artists. Some guitarists show Segovia's playing style include Christopher Parkening, Alex Park and Julian Bream.

The modern school. It is hard to describe this style of playing with the assumption that all guitarists in the same generation would play the same (homogeneity). In fact, it would be impossible to do so, due to the variety of educational curricula/development, or simply just the variety of subjective experience and execution of the piece by these artists. Therefore, it would be more reasonable to say that this school is different from the Segovia school, and that is it. However, it is still okay to have a broad description. Quite contrary to Segovia's style, the newer generation tended to focus on articulation, experimentation and "perfection", thus little rubato or "caressed" tone. With the popularity of guitar competitions, it is even more motivated to achieve such goals. These artists plays with modern style: John Williams, Thomas Viloteau, or Thibaut García.

Though I am aware that there has been a lot of subcatagorization so far (works for strings by Bach, then six sonatas and partitias, then each contain several movements), the famous Chaconne also consists of two smaller parts: first part written in D minor, with a classic 3/4 rhythm of the chaconne dance, solemn and funeral-like; second part starts in D major, tranquil and serene, then ends back to D minor. For the purpose of this review, I excluded the first part of the Chaconne. The review only discussed the climatic section from the second part of the Chaconne. Since there are potentially many different interpretations of this section, this study aimed to collect, describe and characterize different executions by some famous guitarist. To my knowledge, there has been no paper compiling and analyzing at any level of this matter, thus justify the need for this study.

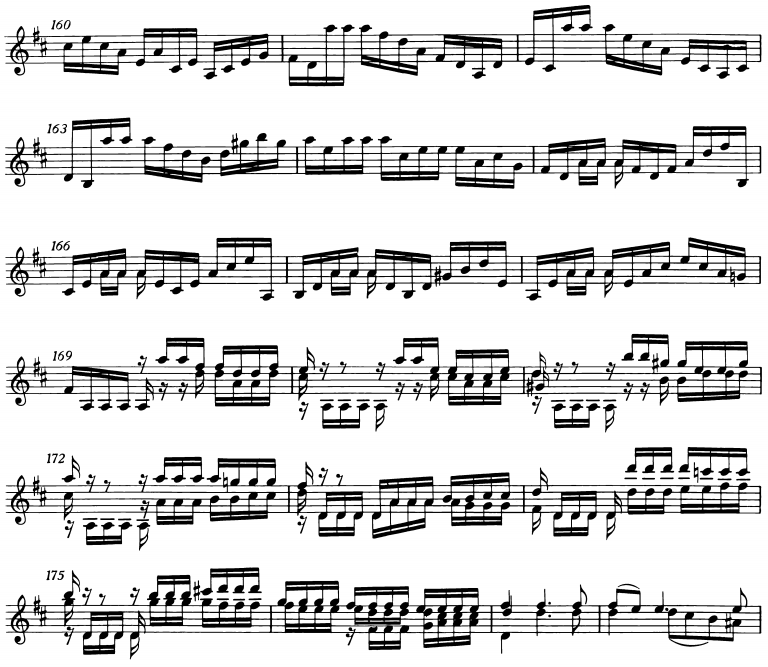

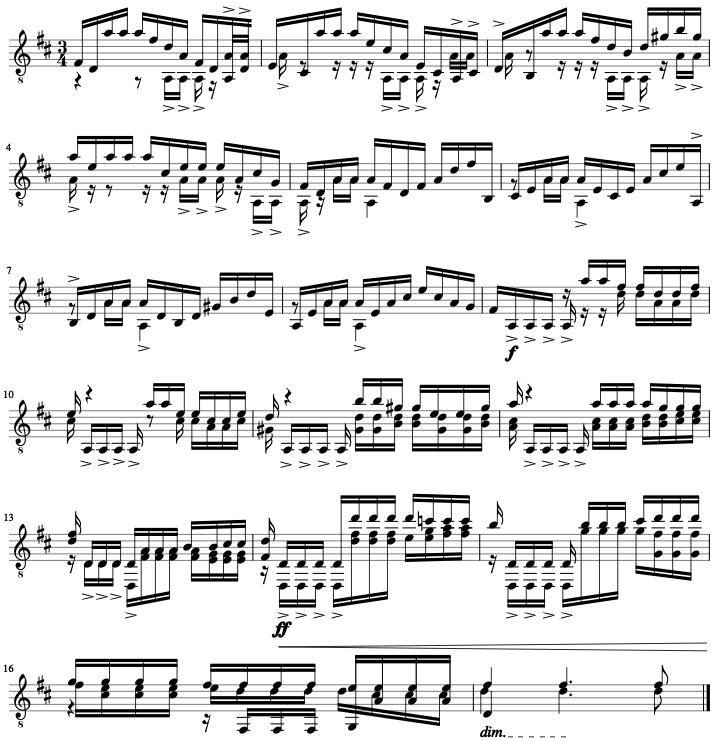

Bar 161–177 (Figure 1) would be the major focus for this review.

Data collection. I gather recordings following convenient sampling. Unlike written literature where there are keywords and therefore search strategies (in academic journals, there are even MeSH terms where you can expand and collapse terms!), there is simply no way to collect music other than by searching for the music manually and listen fully.

I used the terms "Bach, Chaconne, Ciaccona, guitar" as my primary search. I looked for audios and videos on Spotify and YouTube/Vimeo respectively. After a few attempts, I decided that additional terms such as "BWV 1004" or "Violin Partita No. 2" did not pull any more results, or could even hypothetically reduce the number of results since these platforms tend to show results with the exact set of keywords. After finding as many possible results as possible, I searched for the same recording on Spotify for consistency when writing up the manuscript. I only included interpretations from "famous" guitarists, since they are likely to be more consistent (i.e., less varied from this recording to others). Amateurs, like myself, tend to change execution quite a few times.

Data analysis. When thinking about the analysis, I came to the conclusion that since this study is only about the descriptive aspects, transcribing and analyzing the transcriptions would be the most suitable. In general, I slowly deconstructed all interpretations and analyzed them in terms of arrangements, melodic contours, rhythms, structures, timbers and qualities of recording.

It is undoubtedly I had to listen to the original interpretation on the violin (I chose Jascha Heifetz's version as reference). Then for each guitar recording, I first listened with minimal engagement to the whole 15-minute piece as part of my enjoyment and to identify whether the arrangement "feels significantly different" or not. Those which are eligible will be included in the next phase: transcribing. I listen closely, this time with utmost attention, to bar 161 to 177 and write down the music. The transcription then would be used as an intermediate representation for analysis of structure and harmony.

The original. Heifetz stayed true to the piece (Audio 1). his Chaconne has been a long-standing, critically acclaimed version of the piece. Although there are criticisms (here), the online contributors did not commented anything other than some versions that they think "better" than Heifetz's. In my humble opinion, these arguments are merely their subjective preference and stay invalid, or at least inapplicable to this situation of a performer of such caliber. However, in fact, any of the violin interpretation of the Chaconne would be suitable as the reference of this review since the majority of them does not show significant deviation from the scores (maybe except tempo choices). For example, Hilary Hann, Yehudi Menuhin, or Isaac Stern.

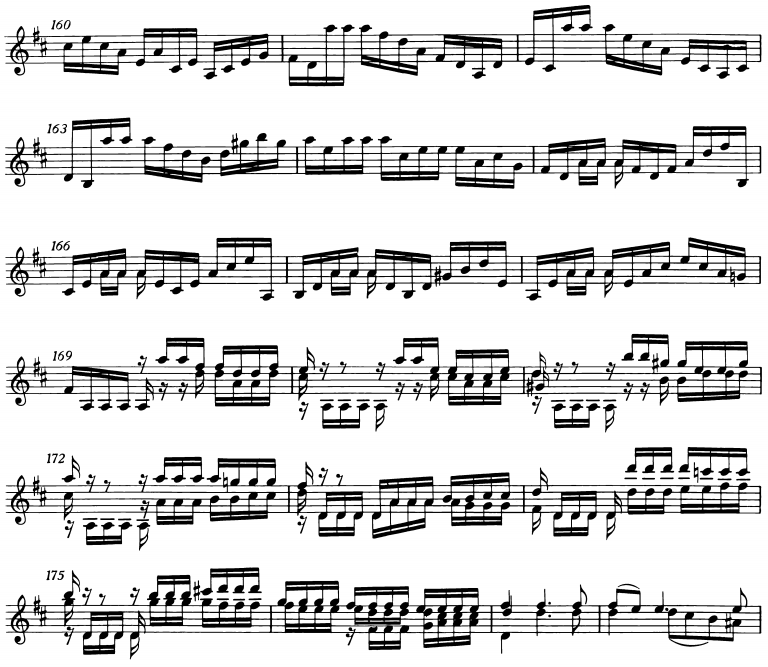

Why is this section the climax? This small section locates after a melodic, lyrical section just after the beginning of the second part (in D major). Keeping up with the adoption of the Chaconne dance, although the "monophonic" writing in this [starting, bar 132–160] section may appear to be played fast and energetically, it would be more suitable to bridge the second part with the tempo used in the first D minor part (almost like a mirroring effect, and the because the structure of the first part suggest this would be a slow piece). Therefore the theme to the second part can be described as: slow, tranquil, serene, calm, peaceful. On a side note, if one decided to listen to the whole piece, apart from the positive feelings, there might be underlying unease, anger, fear or sadness. However, the section of interest suggest a gradual change in harmonic structure, from scales/arpeggios to repeated chords. Despite not being shown explicitly in the scores, the note A was frequently repeated throughout this section, signifying the needs to recognize the emphasis on these "invisible chords". In the key of D major, A is the dominant. The whole section now alternates between three chords: D, A and E7. The E7 chords magnify the effect of the A chords, building up tension, which further requires the resolution to D at the end of this section. Because of this tension, and the resolution at bar 177, this section sets the climax for the second part of the Chaconne. Additionally, the range of voicing is now expanded, associated with quick jumps between high and low registers towards building up higher registers, plus the effect of repeated notes/chords, even make this section more dramatic and create a satisfying resolution (Figure 2).

Some may argue that the arpeggio section (bar 201–208) should be the climax. It can be. However, the effect is not as dramatic (arpeggios versus big chords), and this section serves as the transition back to D minor, so the resolution might not be as pronounced.

Overall themes. Although I did not keep track of the time lapsed listening to all version, I can confidently say I have spent at least 60 hours. There were not so many interpretations that deviate strongly away from the original violin score. They usually kept the integrity of the original structures, notes and harmonies. That is, the main notes from the violin score could still be heard. The duration varied from 2 minutes 16 seconds (Paul Galbraith) to just shy of 50 seconds (John Williams). Such differences in playing duration happened due to the choice of tempo rather than extra passages.

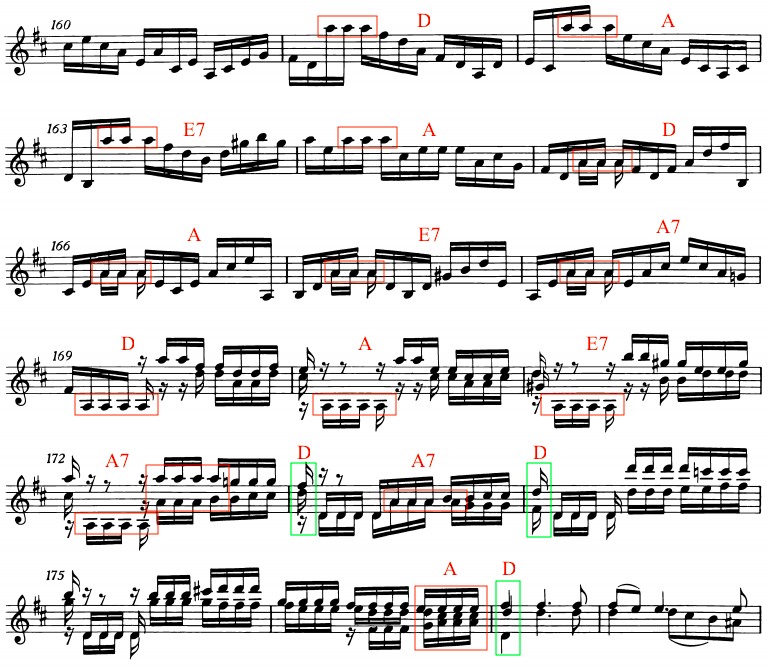

Andrés Segovia: The First. Segovia's transcription of the monumental Chaconne was probably the first world-renowned, to say the least. Debuted on 4th June, 1935 in Paris, his Chaconne has since set the standards for future guitarists. With the privilege of the Internet, now we can easily access his version anywhere online (Figure 3).

Unfortunately, some "Bachian extremists" mercilessly criticized the novelty of the piece: Horror, profanation, disgrace, damnation, murder(!). Arranging the Chaconne from the violin to a different instrument is not uncommon back then. There were many famous composers who had already adapted the Chaconne for the piano (Brahms, Busoni), organ (again, Busoni), piano-violin duet (Mendelssohn, Schumann) or the orchestra (Wilhelmj). Then why transcribing the same monumental work for the guitar was deemed wrong? To say that the Chaconne could only be played [emotionally-correct] on the violin just can't be any further than the truth. An article by Pincherle (1930) justified the marrying between the Chaconne and the guitar:

In the case of the Chaconne, one might at times ask if Bach was not thinking of an instrument of the guitar family. It is surprising that he uses the key of D minor, which is the best key for guitar technique; also that he uses the succession of chords in the last two pages of this work - a succession that reproduces the harmonic scheme used frequently in popular Andalusian songs. And who knows whether the Iberian origin of the Chaconne did not inspire Bach with the idea of using a typically Spanish instrument which he knew and which the masters of time - DeVisee, Campion, Courbet, etc., played?

But the most convincing argument in favor of the Segovia transcription is that it can scarcely be called a transcription. By a singular coincidence (if the preceding hypotheses are not facts) the violin version has no need of any change in order to be played on the guitar. On the contrary, there is on the guitar a fuller realization of those compact chords and those "imitations" which the violin essays to conquer.

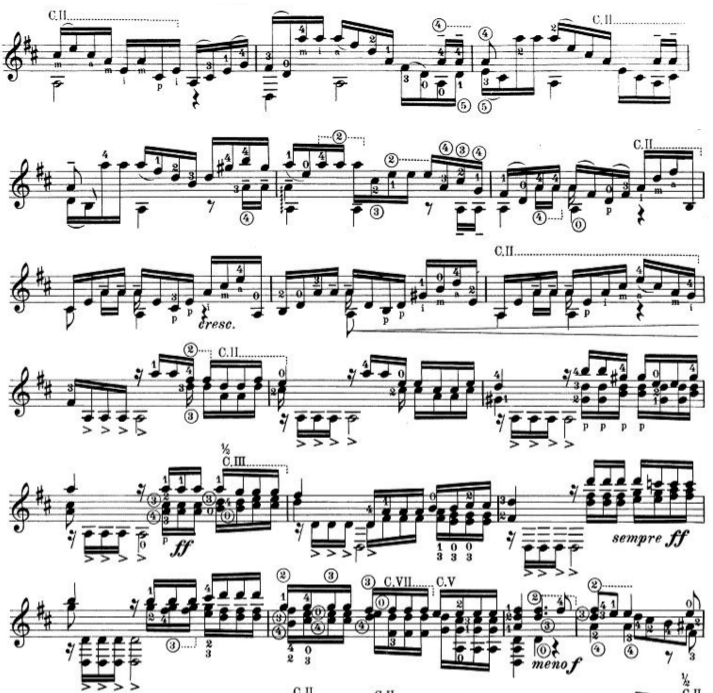

The relationship between the guitar and Bach was yet to be found defenitive however (Wade & Garno, 2000). Though it is true that the notes from the violin score can be played directly on the guitar (we will revisit this later), Segovia did not choose this method. The sound would be too thin since the guitar cannot sustain the notes as long as the string counterpart can. He played with the guitar's forte (pardon the musical pun): chords and polyphony, and this is even more applicable to this section where there definitely chords and polyphony. He added the bass notes (A, which can be played very naturally on the guitar) to indicate the 3/4 rhythm of the chaconne dance; he wrote a one or two more voices, especially when the guitar reaches higher notes (bar 171–176), ultimately inevitably created chords. These chords would be impossible to play on the violin without severe cross-strings, or a specially-made straight-fretboard violin, and that's how this version of the Chaconne is a hallmark piece for classical guitar.

There is one problem for the guitar, however, is the fingerings. Segovia stated in an interview that "every instrument of the orchestra is inside the guitar, but in smaller sound size. It has many different colors and timbres, and it is necessary to develop these qualities of the instrument" (Nupen, 1967). The fingerings, i.e., where on the instrument to play the notes, is the determining factor for the timbres. During the conception of the Chaconne, he must have thought about the production of very specific sounds since Bach's Chaconne is not simply just a piece for violin, remembering it was written not long after his wife Maria passed away, therefore to convey the certain appropriate feels about the piece. He insisted on keeping the fingering so much, even told by one of his students, Christopher Parkening (92nd Street Y, 2015):

I chose to play the 'single greatest piece every written' (the Chaconne) for Andrés Segovia on the third day. I got about a third of the way through the Chaconne, and the next thing I heard was his foot smashing to the ground. Then I stopped playing. I looked up and saw his hands were over his head, and he said 'Why did you change the FINGERINGS?'. His wife was holding him back, and I was melting. He was furious with me.

Segovia could be quite intimidating, and even more so imagining one being his direct student. It could be because of his demand on keeping the fingering, along with the techniques on the guitar, it seemed that almost all his students displayed the Segovian style: Christopher, as we talked, Elliot Fisk or Brigitte Zaczech.

Dynamics marking was very explicit in this transcription as well (Audio 2). A gradual crescendo starts at bar 167, increasing slowly the dramatique of the section. Accented bass notes was clearly a Segovia trademark. His thumb was big and curved, which is very suitable and convenient for producing deep, loud basses (Figure 4).

Generally speaking, despite being controversial, Segovia's Chaconne has changed the way we view the classical guitar, and opened so many possibilities for composing for the guitar.

Narciso Yepes: Post-Segovian. Another Segovia-period attempt was made by Narciso Yepes (1927–1997). On first listen, it may seem that Yepes was heavily influenced by Segovia, evidently in the use of chords, dynamics, polyphony, octavation. However, after listening closely again and again (and even tried playing it), I started to realize that this transcription could be more technically ambitious. Although he (Yepes) added several bass notes to thicken the harmony, similar to what Segovia did, these notes were not at the same particular position (Figure 5). One can easily recognize his guitar, which was not a standard six-string. His ten-string guitar with four added bass strings made it possible to transcribe Baroque music where there are deep bass notes, though might so not be applicable to the Chaconne. Having said that, Yepes definitely went a bit more extreme in the use of chords and octavation, with the full range of the guitar and occasionally extra basses, though the extra strings were a bit redundant doing nothing but merely adding to the resonance of the guitar (Audio 3).

Thế-An Nguyễn, admittedly, is not a famous name, even in Vietnam. He has his own transcription to which when I listen for the first time, it was refreshing and creative, albeit being poorly mastered (severe reverbs and echoes that it messed with the integrity of the music). It was a disappointment for me when I realize this arrangement might not be totally novel, since there are too many elements that were quite similar to Yepes, only with minor tweaks. Inversions of the additional second voice and a small distinction in articulation were all it was. However, the rest of the piece was done quite well to say it has a different feel compared to the mainstream Chaconne (Audio 4).

John Williams: The Energetic. This man is not to be confused with the other John Williams, the composer. The 1969 recording by John Williams was probably when he was still using the guitar made by Ignacio Fleta, and his playing was at his peak. From the recording, it can be heard that Williams respected the original violin version, as he did with the majority of the music he played. A friend of his, Paco Peña stated in his interview that "he (John Williams) appreciates the composer's work, and he somehow has this ability to let the music speak, rather than his own input". This statement stays true to his interpretation of the Chaconne, where there were only the a few notes added, and the musical contour almost stayed the same. This approach was comparable to Brahms' when he wrote the Chaconne for the piano as a left-hand study: both did not see the Chaconne itself lacking or unfinished. There are a few artists adopted this idea, including Thomas Viloteau (will be discussed later) or Thibaut García.

Thomas Viloteau: The Baroque Tuning. It is widely know that the Baroque tuning system is a semitone lower in relation to current/modern standard tuning (ABaroque = 415Hz versus AModern = 440Hz, and A = 432Hz is a scam). The reason might have to do with string tension, where strings could not be too tense otherwise the strings would snap, or worse, the instrument would collapse. Therefore, it is safe to say the the "original" Chaconne that Bach and his contemporaries used to play was in the key of D♭ major or C♯ minor (if we are using modern standard)!

Viloteau's approach, note-wise, was similar to John Williams. Not just Viloteau, other French guitarists also do the same thing. It is unknown whether the coincidence could result from an institutional cause, or from the French artistry which determine how the aesthetic properties of the composition should be played. Nonetheless, sometimes less is more. The fact that the guitar cannot perform certain violin's articulations, such as bowing or sustaining the note, the lower range of the guitar and the tone quality, in my opinion, are some of the areas that the guitar can surpass the violin. The Chaconne is a solemn piece, embeded in polyphonic structure and chords, making it suitable for the guitar. Viloteau's version stood out from the others, largely due to the tuning. Obviously, the guitar was tuned a semitone lower as suggested, but such small difference can lead to a great impact on the perception of the piece. Listening to this, I immediately remembered the "characteristics of all keys" made by Christian Schubart (1806), specifically to the key of D♭ major and D major:

The feels associated with this section, according to the description above would be "of Halleluyahs, of war-cries, of victory-rejoicing". However, revisiting the fact that Bach wrote this masterpiece after his wife's death, would these affections and emotions be applicable? How can one just experienced the pass of a love one, be "heaven-rejoicing"? These notes were writtent in 1806, where we can still say the pitch standard was not yet changed to A = 440Hz and the equal-temperment has not yet be popularized enough to impair the emotional characteristics of a key. Maybe, these notes were to only be used as a reference, though I think a more appropriate portrayal, but ironic, would be in the key of D♭ major, grief and rapture, but things can be better tomorrow Audio 5.

Another aspect which might not be apparent in the section, is the use of Romanticism, referring to the Romantic era of classical music. A Baroque composition, written by a German, but it sounds so French and so Romantic. In Baroque playing, it might be not religiously accurate if there were sudden changes of tempi, dynamics and articulations.

Paul Galbraith: The Solemn. Indeed the harmonic structure suggests that the piece should be played with a slow tempo. The Chaconne's 3/4 rhythm was also derived from the Sarabande dance, which is a slow Spanish dance (we can compare the Ciaccona and the Sarabanda in the Partita). However, one must be aware that reducing the tempo may risk the piece being "dragging" and no long interesting. Paul Galbraith definitely was walking on thin ice here. An average performance of the Chaconne lasts for 14 to 16 minutes; Galbraith's version lasts for just shy of 20 minutes. Another aspect to consider is the variety of tempi used, while others varied the tempo depending on the "variations of the Chaconne form", Galbraith's tempo is almost consistent throughout the whole piece (Audio 6).

There are only small deviations from the original score during the section, however, the drastic change in tempo is worth the mentioning in this article. To compensate to the slow tempo, he has to fluently articulate the sound (subtle use of dynamics and articulations) to maintain the attention to the piece.

Similar to Yepes, Galbraith's guitar is not an ordinary instrument. The Brahms guitar has an extra bass string and an extra treble string (Figure 6). It is reasonable that the difference in the anatomy of the instrument resulted in the transpose of the piece to E minor, rather than D major. The adjustment is unlikely to be relevant to the tuning standards as Viloteau's.

Carlo Domeniconi: The Sacrilegious. The contemporary era is truly a confusing time for classical music. While the transitional stage from Romanticism to early Contemporary was packed with new, refreshing and experimental ideas, the later stages seem to be saturated with music not for the sake of music anymore (not to demerit the high-esteemed composers out there). The Chaconne by Domeniconi is truly a novel take on a masterpiece. I neither dare to transcribe the music, since the harmony is well beyond my capabilities, nor question his intention in producing such music. He stated in an interview with Turell (2019):

Turell: One of your works that I find really wonderful and touching is the Chaconne [based on Bach’s famous Chaconne, BWV 1004]. It is like a contemporary commentary on Bach’s work and it deepens the understanding and experience of it, yet it’s an outstanding, excellent piece of its own. How did you come up with this idea: using Bach’s Chaconne as a kind of a starting point or matrix for your composition?

Domeniconi: Every transcription of the Chaconne presents serious problems. My idea was to see what would happen if I didn’t have to worry about style, the rules of counterpoint, etc. What happens is this: reveling in pure anarchy. Ferruccio Busoni’s arrangement for four-hands piano purposely doesn’t respect the rules of Bach’s time. My Chaconne takes this a huge step further in disregarding even the notes. The only thing left of the original is the recognizable structure.

The climatic section is not an exception when it comes to the chaos of the transcription. While I dearly respect the creative attempt in making the Chaconne a piece of the late 20th century, in my opinion it is musically substandard, though it might be fun and enlightening to listening to (Audio 7).

Above we discuss six different interpretations of the same section. After an exhaustive search, I concluded that other versions could be either the same or some types of iterations of the aforementioning ones. This is not to say that these six versions were the first and all other editions are only emulating from the originals. In fact, it is unknown whether the ideas actually started from a person, or whether they converge independently (great minds think alike). Nonetheless, I have a strong feeling that Segovia's version may have inspired many to adapt the transcribing styles, thus explain the similarities between some versions of the Chaconne.

There is no version that is the best. Superlativity in performance arts is often overrated, and a luxury we can never achieve. The perception of sound follows a individualistic manner, that is everyone perceives sound differently. There are many factors that potentially influence one's aural ability: genetic factors, educational background, socio-cultural exposure, psychological state, etc. The more valid conclusion is that these different interpretations have contributed the the body of knowledge of music, each with different intentions in terms of the use of harmony, dynamics, articulations, playing style, or tuning system, techniques. The cummulative result may lead to some equally beautiful version of this all-time masterpiece.

There were several limitations. The one that bothers me the most is the fact that I was not a formally trained muscal theorist, or that I am a professional instrumentalist. The purpose of the study is only to compile and analyze, using my own knowledge, different versions of the Chaconne. Another limitation is the sample size of the study. I only included six interpretations, all from famous artists, while there could be other pre-professional performers that may have a version of the Chaconne of their own, waiting to be shared, and unfortunately was not included in the study.

Haußwald, G. (1958). J. S. Bach (composer) Violin Partita No. 2 BWV 1004. Serie VI. Kammermusik, Band 1. Kammermusik 1: Werke für Violine (pp.30-41)

Nupen, C. (1967). Segovia at Los Olivos. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1QV_56-9flA

Pincherle,, M. (1930). William Cumpiano's Segovia Page: The Chaconne. Retrieved on 27 February 2020.

Schubart, C. (1806). Ideen zu einer Aesthetik der Tonkunst. Translated by Rita Steblin in A History of Key Characteristics in the 18th and Early 19th Centuries. UMI Research Press (1983).

Segovia, A. (1934). J. S. Bach (composer) Violin Partita No. 2 BWV 1004, Chaconne. Schott, Germany.

Turell, A. (2019). Between Cultures: A Rare Interview with Visionary Composer and Guitarist Carlo Domeniconi. Classical Guitar Magazine

Wade, G. (1985). The guitarist's guide to Bach. Gortnacloona, Bantry, Co. Cork: Wise Owl Music.

Wade, G., & Garno, G. (2000). A new look at Segovia, his life, his music. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay Pub.

92nd Street Y (2015). Christopher Parkening on Andrés Segovia: Guitar Talks with Benjamin Verdery.